The creation of Grateful Dead music video “Hell in a Bucket,” particularly during its MTV era, unfolded as an unexpectedly surreal and memorable event, meticulously documented by Len Dell’Amico, the band’s designated film and video specialist, in his memoir, “Friend of the Devil.” His recollections paint a picture of a period – 1980 to 1995 – saturated with “love, chaotic energy, and significant quantities of cannabis,” as he described it.

Dell’Amico’s account centers around a particularly bizarre incident during the filming of the video. The visual centerpiece involved a trained duck, initially brought in at the urging of founding member Bobby Weir, who was then brimming with enthusiasm and perceived as “a god.” Weir requested a tiger as well – a nine-foot Bengal weighing 400 pounds – further adding to the already eccentric atmosphere. The duck’s behavior quickly escalated; it became captivated by Weir’s glass of champagne, repeatedly dipping its beak in for sips until it was visibly intoxicated and slumped over.

“It looked like we had a trained duck,” Dell’Amico remarked, initially amused by the spectacle. However, the situation swiftly spiraled out of control when the duck’s trainer contacted him with an “irate” phone call, expressing profound distress about the animal’s excessive consumption. The duck’s subsequent aversion to white grapes – revealed as the catalyst for its indulgence – added another layer of comedic complexity to the story.

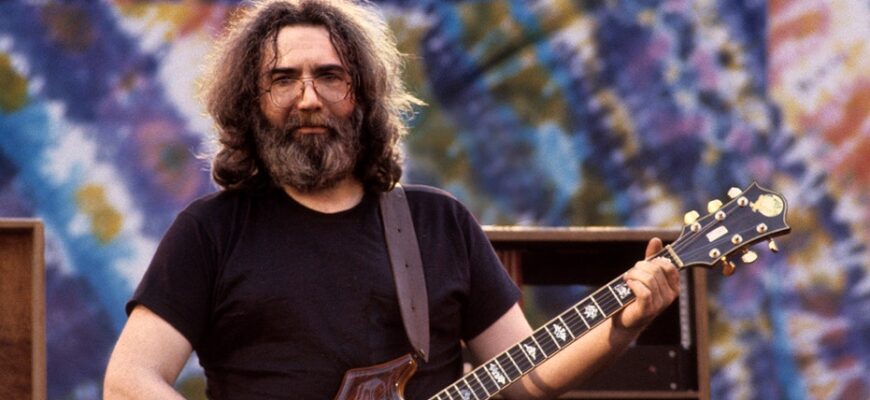

Beyond the duck, Dell’Amico offered a revealing portrait of Jerry Garcia himself. He characterized Garcia as possessing a quiet intelligence and remarkable humility, often preferring genuine connection to celebrity status. “You might think that’s easy,” he stated, “but it’s not when you’re that famous.” Garcia shunned extravagant displays or self-promotion, famously stating, “I’d rather do things than have things.” He was a captivating individual—a “charm machine,” as Dell’Amico termed him— deeply interested in spirituality and philosophy.

The recording sessions were filled with moments of genuine connection. Dell’Amico recounts dinner conversations where Garcia would insist on paying, offering to distribute free meals to those in need. The interactions revealed a man profoundly unconcerned with fame and fortune, prioritizing simple pleasures and human compassion. He was a “fearless” individual who embraced life with an open heart.

Ultimately, Dell’Amico concluded that Garcia’s life, despite its brevity and struggles, wasn’t defined by tragedy. “Calling him broken would be crazy,” he stated. “He did more than most people do in 53 years.” His perspective underscored the enduring legacy of a musician who prioritized living fully, embracing both joy and sorrow, leaving behind a profound impression on all those who knew him.